How Text Data Can Improve (or Worsen) Business Decisions

Marketing, sales, and product teams often need to answer questions such as "does price impact customer satisfaction scores?" However, these types of questions are difficult to answer directly because other factors, such as item quality, may cause an item to be both more expensive and more highly rated. In other words, variables like quality may confound the relationship between price and satisfaction.

Fortunately, these teams often have reams of text data from sources such as outreach campaigns, social media posts, and open-ended reviews from which they can extract confounding variables, like quality. This post shows how we can use text data to improve our inferences about the relationship between important variables. But it also shows that if we aren't careful with our analysis, we may end up making our estimates even worse.

The basic problem #

To motivate the post, assume we want to infer the impact of price on a customer rating. In addition to the price and the rating, we also have the customer's open-ended review. The table below provides an example piece of data:

Example Review #

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Price: $$$$$ (5/5)

Review

The grass-fed Wagyu ribeye, with perfect marbling, was fantastic. Although it was expensive, like everything else these days, the experience was amazing.

Phrases like "Perfect marbling" and "grass-fed ribeye" provide information regarding quality that we can extract and use to adjust for confounding. But the review also contains information about many other concepts. The table below provides an incomplete set of the concepts we could extract, along with the relationship these concepts have to price and the rating.

Concepts from review #

| Text Element | Extractable Concept | Impacts Price | Impacted by Price | Impacts Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| grass-fed Wagyu ribeye, with perfect marbling | Quality | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| fantastic.. the experience was amazing... expensive | Overall Sentiment | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| expensive, like everything else these days | Economic inflation | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

Legend: ✓ = Yes, ✗ = No

The table shows that in addition to quality we can also extract information on the review's overall sentiment as well as a macroeconomic concept, economic inflation. We can also see that overall sentiment is, in part, caused by price and sentiment also impacts the rating. Economic inflation impacts the price, but it is only through price that it impacts the rating.

If we include features that capture sentiment and inflation, without making other adjustments, we can end up with even more biased estimates of the relationship between price and the rating than if we just ignored the text data completely.

How we can use text to improve, not worsen, our inferences #

We have two standard approaches to extract information from text to include in our model. The first approach is to predefine a concept, such as quality, and then instruct an LLM (or human labelers) to annotate whether the concept exists in the text and, if it exists, to provide some score regarding the strength of the concept. These scores are typically coarse and somewhat arbitrary. For instance, quality would be defined as something like as "high, medium, low".

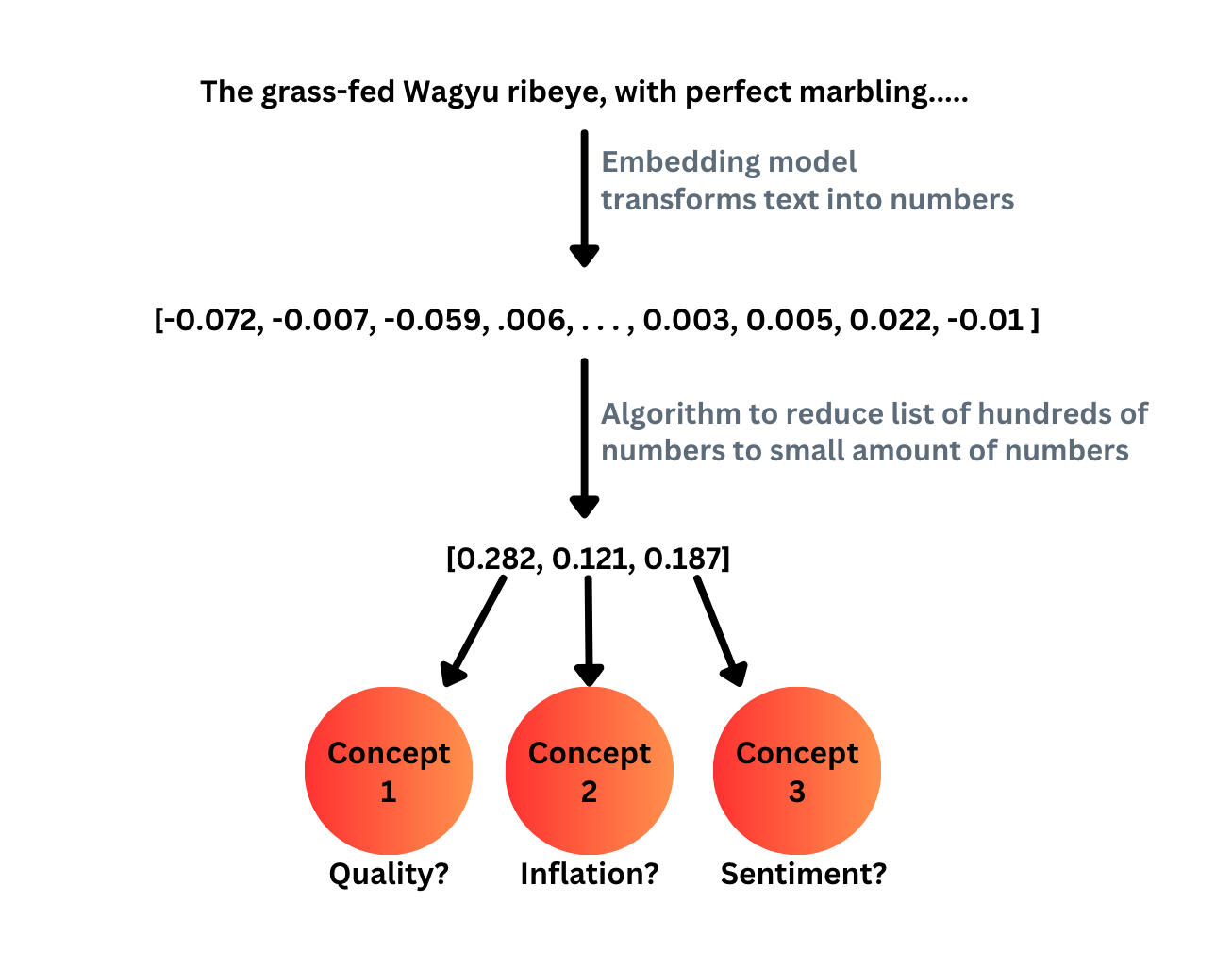

The second approach is a bit more involved and is described in the figure below.[1] This approach has the benefit of automatically extracting concepts from the text as well as providing more precise scores -- real numbers instead of a label like "high".

To walk through the approach above, we start with an embedding model to transform the text-review to a vector of numbers. Then, since this vector will be large -- OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small is 1,536 dimensions -- we typically apply some algorithm to reduce the vector space down to something smaller. For our purposes, lets suppose we were able to reduce the embedding space down to 3 dimensions. Unlike in the first approach, where the text would be classified as something like high here we would get different numbers for each observation. One observation may get [0.2, -.5, 1.2], while another gets [.1, .5, -2]. This is much more fine grained than a label like high and we don't have to explicitly instruct the model to search for something like "quality". For these reasons, the second approach is much more attractive than the first.

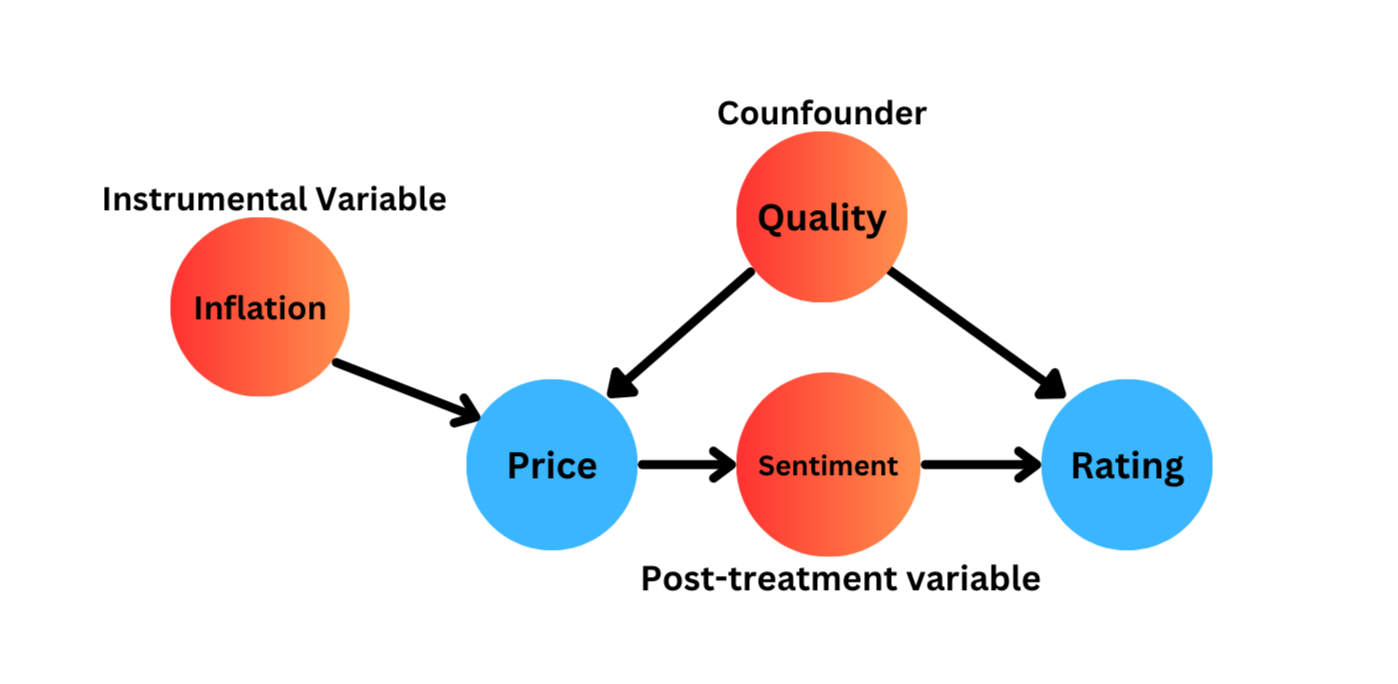

But the drawback of this approach is that we don't actually know what concepts we extract from the text -- dimensionality reduction doesn't come with a label -- nor how these concepts are related to the variables we care about. But for clarity, let's assume we do know what these concepts are. The figure below assumes that we extract "sentiment", "inflation" and "quality" from the text. It then shows how these concepts relate to price and quality.

If we simply include these values in our model, there are at least two cases where we would end up with worse estimates than if we ignored the text altogether. These areas are post-treatment bias, which would arise from using sentiment, and bias amplification, which would arise from using economic inflation.

Post-treatment bias #

Suppose we included overall sentiment in our model. From Figure 2 above, we can see that price only impacts the rating through its impact on the customer's overall sentiment. Since price's impact on the rating is fully absorbed into overall sentiment, including this concept in our model would lead us to infer -- incorrectly -- that price is unrelated to the rating.

Therefore, if our process of transforming raw text leads to concepts that enter the model in a way that cuts between the variable we care about and the outcome, we need to be careful to not include it.

Bias amplification #

The second issue is more nuanced, and arises when we include a variable that is strongly related to our predictor variable and only weakly, or not at all, related to the outcome variable. There also needs to be some unobserved confounding variable. Imagine a version of Figure 2 that only included "inflation" and "quality" along with "price" and "rating".

Since inflation and quality both impact price, including both in the model makes them statistically dependent. This leads inflation to have a non-causal, confounded, path to the rating. Since inflation is now confounded, our estimates for price will be even more confounded than if we had just left inflation out all together. This concept is known as bias amplification and although it receives much less attention than issues such as post-treatment bias and confounding, it can similarly bias results. As (Pearl (2010)) notes, bias amplification is especially likely when estimating propensity scores, which is common in analyses using text.

What to do #

To use text to improve, and not worsen, our inferences we need to reduce the dimensions of the embeddings jointly with the model that we want to estimate. Using figure 2 as an example, we can to extract concepts that align with the confounder, instrumental variable and post-treatment variables. By extracting only these concepts from the review we could then estimate the correct model for our purposes.

But if we aren't careful of how the concepts we extract from text fit into the overall model we are trying to estimate, we may end up with something even worse than if we had ignored the text data in the first place.

Conclusion #

Companies are sitting on mountains of text data. By appropriately incorporating it into our models, we can answer important questions for teams across the organization. But failing to account for how the concepts we extract from the text data relate to the question may lead to even worse inferences and worse decisions.

Footnotes #

Another version of this approach is to use the text embedding to estimate a propensity score (Weld et al. 2020). But notice that concepts such as inflation and sentiment will be highly predictive of the price and may look like attractive predictors. Including these variables in our propensity score model will cause the same issues as that outlined here. Using these embeddings directly give us no sense of where the features fit into our causal model. ↩︎